Screen shot from Google Street View

Heritage College in Wichita, Kansas, is one of 10 campuses that closed without warning on Nov. 1.

On the day Heritage College and Heritage Institute closed their 10 campuses, Dr. Joshua Hatch was in Fort Myers, Florida, teaching a class in surgery and anesthesia to students studying to become veterinary technicians. Suddenly, administrators interrupted the class. They sent the students home and called faculty to an emergency staff meeting.

There, employees were stunned to learn that the company behind the for-profit vocational school was closing, effective immediately. “They gave everybody a single check for minimum wage for the last two weeks, which did not fully cover the [time] that was actually owed,” Hatch said.

As disappointed as he was to lose his job, Hatch’s greater heartache is for the students.

“The students are the ones it’s most unfair to,” said Hatch, who became a teacher after 11 years in small animal practice. “I can get a new job, cut some coupons, make ends meet. They were the ones who were told, ‘This is how you better yourself; how you support your family and make a better life for yourself.’ That seems to be the great injustice and shocking part of it all. …

“From what I’ve found,” he added, “nobody is doing anything to protect them or really work with them.”

Interviews with affected students support the impression that they were left largely on their own to sort out whether they could salvage their schooling and investment in a program that cost $30,000. Should they try to transfer? If so, to where? Will their class credits be accepted by another program? Can they get their money back? How should they manage their educational loans?

“Most of us are so young. I’m only 26,” said Caila Spitzer, who was four months short of completing the 20-month veterinary technology program at Heritage’s Wichita, Kansas, campus when the school shuttered. “I wouldn’t even know where to start. People are like, ‘Are you calling around?’ I don’t know what to say.”

Following the Nov. 1 closure, the U.S. Department of Education posted fact sheets with guidance tailored to students in the states where Heritage operated — Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio and Oklahoma. The four-page documents provide names, addresses and contact information for each state’s relevant education agency; email addresses for Heritage through which to request transcripts and other school records; and general information about discharging federal student loans or transferring to another program.

About veterinary technology

Beyond that, there appears to be little available to guide former students. Heritage dismantled its website, leaving only a home page with a statement that the 30-year-old institution was closing permanently. The statement explains:

“The reason for the campus closures is that Heritage does not have the cash to continue to run its business. Numerous factors contributed to the circumstances, including declining student population and a continued, decreased demand for the services of for-profit schools. Heritage did not close due to wrongdoing or a forced closure by a regulatory body, and we did explore a range of options that would have enabled the campuses to remain open serving students. Unfortunately, the options were not viable and our efforts proved unsuccessful.”

The downfall of Heritage is one in an ongoing string of failures among for-profit career schools. A USDE webpage headed “Has Your School Closed?” shows 21 institutions shuttered since October 2015. The list includes schools whose closures attracted national attention, such as Corinthian Colleges in April 2015 and ITT Technical Institutes last September; and a number that drew less widespread notice.

Driving the trend in closures, at least in part, are federal regulations known as gainful employment. Effective as of July 2015, the rules require postsecondary career-training schools to demonstrate that students receive a reasonable return on their investment in education. That value is measured by graduates’ debt-to-earnings ratio. School programs risk losing eligibility to participate in federal student-aid programs if their graduates’ typical loan payments exceed 20 percent of their discretionary income or 8 percent of total earnings.

Failing the government accountability standards is a problem for any institution with a student body comprised mainly of borrowers who rely on federal student aid for their tuition.

On Jan. 9, the USDE released the first debt-to-earnings rates for the nearly 8,700 certificate and degree programs subject to the rules. The agency reported that 803 programs serving hundreds of thousands of students failed the accountability standards. Another 1,239 were placed on a probationary status. Of the programs that failed, 98 percent are run by for-profit institutions.

Programs that fail twice within three consecutive years lose eligibility for federal student aid. Those on probation, called “zone,” have four years to improve before becoming ineligible.

Among programs in jeopardy, 29 were Heritage programs in Fort Myers and Jacksonville, Florida; Denver; and Oklahoma City. None was a veterinary technician training program.

That's what caught Hatch and his co-workers off-guard. He and other faculty on the Fort Myers campus were aware that parts of the system were struggling but "they’d told us that our campus was doing well, and our program was one of the best, financially, in the system," he said.

Heritage College and Heritage Institute were operated by Weston Educational Inc., a privately held company based in Colorado. According to a local media report, the company is headed by Earl Weston, owner of Weston Auto Gallery, which sells used luxury and sports cars in Fort Collins. The VIN News Service was unable to reach Weston. A manager who answered the telephone at the dealership said he had no way of reaching Weston and that he did not keep a regular schedule at the business.

Weston Educational filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in late November.

The company’s registered agent and one-time CEO, Eric Chiusolo, was elected board chairman of the trade association Career Education Colleges and Universities in June. The association’s communications manager, Allison Brown, declined to comment on the trend in private vocational college closures and did not respond to a request for assistance in contacting Chiusolo.

33 accredited vet tech programs closed since 2014

The American Veterinary Medical Association Committee on Veterinary Technician Education and Activities (AVMA CVTEA) is the nation’s sole accreditor of veterinary technology programs. Completion of a CVTEA-accredited program qualifies aspirants to take the Veterinary Technician National Examination, a credentialing test required by most states.

Since 2014, 33 of the more than 200 programs accredited by the CVTEA have had their accreditation withdrawn, according to information provided by the AVMA. More than half of the withdrawals happened in 2016. All were caused by program closures. Almost all of the programs that closed were operated by for-profit schools.

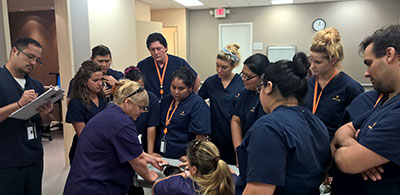

Photo by Dr. Joshua Hatch

Instructors Maureen McNamara and Dianne Waunsch (in purple scrubs) show veterinary technology students restraint and blood-draw sites on a rabbit. These students, photographed during the 2015-16 winter semester at the Heritage Institute campus in Fort Myers, Florida, were able to complete their training. Students who followed them the next year were not as fortunate.

Some unlucky students reportedly have been twice hit by school closures. Melanie Beekman, who was studying at Heritage’s Fort Myers campus, knew of one classmate who was at ITT Technical Institute when it shuttered two months earlier. In despair, the classmate said, “I can’t do this again. I can’t do this again,” Beekman recounted.

Beekman’s own enrollment at Heritage was driven somewhat by chance. At one time, she wanted to become a veterinarian but “life happened,” including the birth of two children. She worked in various jobs — as a maintenance technician at a water company, a server and a UPS driver. None ignited a passion.

Talking one day to her boyfriend, with whom she is raising a combined family of six children, Beekman mused: “I’ve always had a heart for animals. I wonder if there are any schools around here that have to do with that.”

She turned to Google, which pointed to a veterinary technology program at Heritage in Fort Myers, a half-hour drive away. In July 2015, she enrolled in the 20-month program, taking classes five days a week. She completed all but one class and an externship when her education came to an abrupt halt.

Beekman was so bitterly disappointed that she barely could talk about it at first. “I basically wasted two years, almost two years, of my life when I could have been working and helping my boyfriend out instead of following my hopes and dreams that could better my family, and have nothing to show for it,” she said.

Compounding the insult, Beekman subsequently received bills on a private loan she had taken from Heritage to pay for the part of the $30,000 program cost not covered by federal student aid. “I’m not giving it to them,” she declared. “...There’s no school!”

Photo by Devehn Spitzer

Caila Spitzer was four months shy of completing the veterinary technology program at Heritage College-Wichita when the school closed. After two months of receiving conflicting information, she was able to cancel her private educational loan from Heritage. Spitzer is pregnant and had expected to be done with school before the baby, due in late February, is born. She hopes to resume school after adjusting to being a new mom.

Spitzer, the student in Wichita, had a similar experience. Agents from Heritage’s loan servicer, TFC Tuition Financing, called her repeatedly in the month after the school closed, pressing for money.

“I cannot justify paying them for an education I didn’t receive. I can’t,” Spitzer said. “They want me to pay the school that’s no longer in existence. They don’t even have a website. It’s nuts!”

Loan cancellations possible

Reached in mid-January, TFC’s manager of client development and retention, Shameka Savage, told the VIN News Service that Heritage borrowers could close their accounts by submitting a copy of their transcripts showing withdrawal from the program on or around the Nov. 1 closure date.

“Heritage is advising us that they no longer owe a balance,” Savage said.

She said TFC had not yet received transcripts from all affected borrowers and she could not predict how long it would take Heritage to provide transcripts to former students. She declined to say how many borrowers were affected.

As for students who have requested but not yet received transcripts from the school, Savage said, “We’re not saying they do not have to pay.” Asked what those borrowers should do, she declined to provide general guidance. “Any student who has a question about their account, they just need to contact us and we would advise them about their particular account,” she said.

Savage noted that borrowers who completed their schooling or withdrew before the school closed remain obligated to repay their debts in full. She said some have expressed to TFC that “they feel as though they should not owe it,” but they do.

Affected students may discharge their federal educational loans, as well. USDE guidance on loan discharge states that borrowers eligible for loan discharge include those who withdrew within 120 days of a school's closure, in addition to those who could not complete their programs due to closure.

Students who are able and choose to transfer their academic credits or hours to another program are ineligible for federal loan discharge.

Transferring credits a complex issue

Sorting out whether transferring is feasible is a potentially complicated question. Spitzer, for example, inquired at Wichita Area Technical College about transferring Heritage credits to WATC’s brand-new veterinary technology program. She said she was told that “we can’t validate that what you learned was enough for our curriculum.”

She was stunned by this reply because before she enrolled at Heritage, she made certain it was accredited by the AVMA CVTEA. Moreover, the program to which she considered transferring is new and as yet unaccredited.

Laura Lien, assistant director of education and research at the AVMA, said the decision on accepting transfer credits rests with individual institutions. The CVTEA accreditation standard regarding credit transfers requires only that programs and institutions publish their policies on transfer credits.

Amanda Hackerott, program designer and director of WATC’s veterinary technology program, explained that the problem for ex-Heritage students is that their institution was accredited by the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools, which works largely with for-profit schools.

WATC, a public school, is accredited by The Higher Learning Commission, an accrediting body for postsecondary schools in the north-central United States. Hackerott said credit transferability is governed by accreditation of the institution as a whole rather than accreditation of individual programs.

Hackerott called the credit-transfer problem “a one-two kick in the stomach” for students stranded by Heritage. Having taught at Heritage’s Wichita campus before moving to WATC in June, she said, “I know a lot of them personally,” and added regretfully, “then they come to my institution and I wish I could do more, but I can’t.”

Hackerott said a dozen or so students have decided to start over at WATC. Because they’re not trying to transfer credits, they are eligible to discharge any federal loans they may have, she said. WATC has been helping students file the necessary paperwork to discharge those loans and reapply for federal financial aid at their new school, she said. (Costing about $16,000, WATC’s two-year veterinary technology program is significantly less expensive than Heritage’s.)

A for-profit online school, Ashworth College, has made a special effort to try to accommodate Heritage's stranded veterinary technology students. In a letter sent to former Heritage students who inquired about transferring, Margi Sirois, the veterinary technology program director at Ashworth, said the school was prepared to offer transfer credit to students who pass a 50-question multiple-choice exam on each course for which they’re seeking credit (excepting four courses with a clinical component).

Ashworth also has earmarked scholarships for former Heritage students. “Students that were nearly finished at Heritage will be given preference for full scholarships, and partial scholarships are available for a limited time for all others,” Sirois wrote.

While Ashworth’s online training could be a convenient option for many, its veterinary technology program is not yet accredited. It has applied for accreditation but an initial site visit by the AVMA CVTEA is not scheduled until February 2018.

Legal action

The federal court system database shows Weston Educational Inc. named as a defendant in four civil suits, including a class action pursued by former employees alleging violations of federal and state laws relating to proper notice of impending mass layoffs and payment of wages. The plaintiffs say employees were not paid the wages they earned in the final three weeks.

According to the suit, Heritage’s enrollment of about 5,000 students in 2013 dropped to 1,800 students by 2016. The suit says the institution had 600 employees when it closed. It identifies veterinary technology as the school’s largest program.

The suit alleges that a series of changes began in 2014 when Chiusolo was hired as CEO, including the replacement of senior managers, large staff layoffs and significant changes to curricula, “slashing the number of credits and amount of content being taught …”

Enrollment dropped and financial difficulties followed, the suit alleges. For example, it states: “[T]he Little Rock campus had its utilities turned off twice, one in June and once in September 2016, due to nonpayment.” It goes on to say that the Columbus, Ohio, campus was served an eviction notice because the school hadn’t paid its rent.

During the last week of October, “CEO Eric Chiusolo left the company and was escorted out of the building,” the suit states. On Friday, Oct. 28, “Earl Weston appeared at a meeting of the employees at the Denver Facility, and addressed them as Heritage’s chief executive.”

The suit continues: “Mr. Weston told the gathered employees ... that Heritage was unable to pay their salaries due to a lack of funds. Weston said that employees would receive less than their full paychecks for the pay period of October 8-22, 2016. [He] stated … that, although he was ‘not a rich man,’ he personally paid a million dollars to cover payroll because Heritage lacked funds.”

Weston allegedly said nothing at the meeting about closing the schools. Operations ended four days later.

Editor’s note: The article has been changed from the original to correct a statement that Eric Chiusolo is board chairman of Career Education Colleges and Universities. Chiusolo assumed the post in June 2016 but no longer is in the position for reasons that the CECU has not explained.